The career of every great rock hope comes wildly front-loaded, but rarely as drastically as The Strokes’. The quintet exploded out of Manhattan at the dawn of this millennium with an achingly cool design classic of a debut album that they’ve never come close to matching. Two decades later, they ...

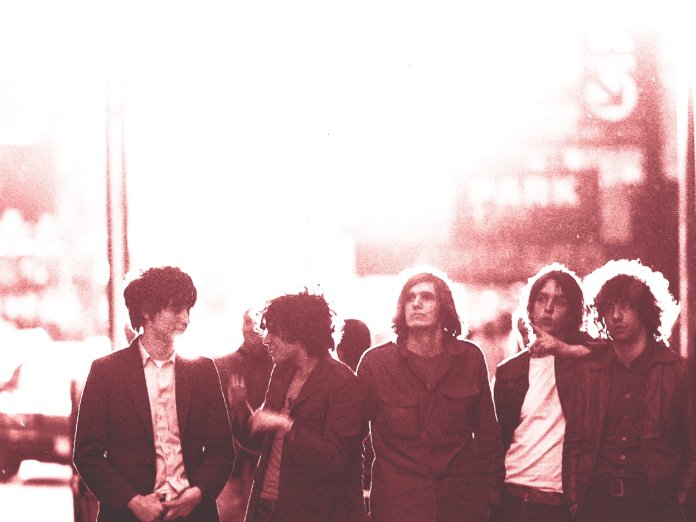

The career of every great rock hope comes wildly front-loaded, but rarely as drastically as The Strokes’. The quintet exploded out of Manhattan at the dawn of this millennium with an achingly cool design classic of a debut album that they’ve never come close to matching. Two decades later, they are actually deep into a respectable second act, though it seems they will never again hit the same heights they enjoyed when first conquering the world as the last in a long line of iconic skinny-jeaned NYC rockers stretching back to the Ramones, Television and The Velvet Underground.

The Strokes were unlikely rock stars. Educated at elite private schools, they were products of gentrified Manhattan rather than the city’s grungy downtown history referenced in their archly retro image and music. All the same, they looked and sounded fantastic, astutely reviving a stripped-down garage-rock aesthetic in an era when bloated nu-metal and slick dance-pop dominated the US charts. Their meticulously constructed songs were lean, propulsive and addictive, providing a beautifully stark sonic canvas for those sublime moments when Julian Casablancas broke out from monochrome yelping into cascading, Technicolor croon. The singer’s voice, cloaked in distortion by producer Gordon Raphael, felt deliciously analogue in an age of diamond-sharp digital production. This fuzzy-warm vintage-vinyl sound was no accident. Their record label demanded a cleaner, fuller mix of the debut album but they rightly insisted on keeping it shabby-chic.

Heard today, denuded of media hype and honeymoon hysteria, how do the band’s opening run of singles and B-sides hold up? Mostly pretty well. “Last Nite” remains a commanding, kinetic pop-punk blast with its jittery Bo Diddley beat and sly melodic homage to Tom Petty’s “American Girl” (which led to Petty graciously inviting The Strokes on tour a few years later). “The Modern Age” and “Hard To Explain” have a sleek linear velocity, with inevitable echoes of veteran NYC rock legends but also some of the elegant modernist thrum of early New Order. Among the B-side tracks, the stand-outs are the rough, truncated home-demo versions of “Last Nite” and “Is This It”, the latter a dreamy Wurlitzer whirl of woozy moans and unwinding music-box chimes. These skeletal rhythms and staccato guitar lines may flirt with postmodern pastiche, but they still proved fresh and vital enough to inspire a thousand new guitar bands, from The Libertines to Arctic Monkeys to Vampire Weekend.

When they reconvened to make Room On Fire in 2003, The Strokes were the world’s hottest musical property, with all the pressures and tensions that brings. After scrapping early sessions with Radiohead producer Nigel Godrich, they reconnected with Gordon Raphael, recapturing some of their old studio chemistry. But the recordings were rushed, and most reviewers lamented the lack of any major musical progression, the polished blasts of singles “12:51” and “Reptilia” already sounding like a more conventional indie-rock band. The long shadow of the first album also lingers, especially on “The End Has No End” with its undulating echoes of “Is This It”. The flipside tracks are fairly uneven too, especially a predictable live cover of The Clash’s “Clampdown”, recorded at London’s Alexandra Palace. The only pleasingly leftfield twist here is the Regina Spektor duet “Modern Girls & Old Fashioned Men”, which allows Casablanca to fully flex his jaded romantic crooner side.

Third album First Impressions Of Earth scored The Strokes their only UK No 1 to date, but still sold considerably less than its two predecessors. Once the band’s sole control-freak songwriter, Casablancas began to share credits at this point, which arguably diluted their idiosyncratic charm. After firing Raphael early in the sessions, they brought in Grammy-winning producer David Kahne (Paul McCartney, Tony Bennett) and seasoned heavy rock mixer Andy Wallace (Nirvana, Slayer), which helps explain the beefed-up, clobbering feel of singles like “Juicebox” and the shiny stadium-pop anthem “You Only Live Once”.

The B-side tracks feature a radically different demo sketch of the latter, originally titled “I’ll Try Anything Once”, in alluringly intimate late-night piano-ballad form. The blandly adequate cover of Marvin Gaye’s “Mercy Mercy Me (The Ecology)”, which features famous friends Eddie Vedder and Josh Homme, is a ballsy inclusion. The Strokes spent the rest of the 2000s on hiatus, mostly working on solo projects. This was not the end of their story, but undoubtedly the end of their imperial phase.